Scientist, fisherman team up to restore shellfish habitat

By Elise Clouser

In the face of a changing coastal environment, a local scientist-fisherman duo is working to help restore oyster populations in Carteret County waters.

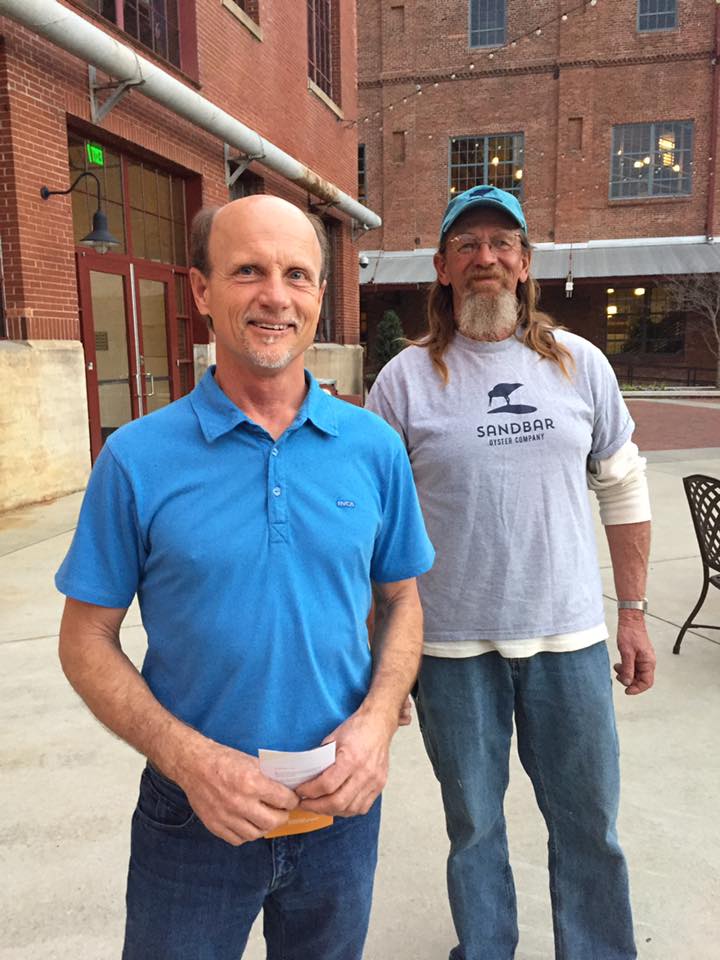

Dr. Niels Lindquist, a researcher at the UNC Institute of Marine Science, and David “Clammerhead” Cessna, a longtime commercial fisherman, are business partners who have created a new, biodegradable material to grow oysters. Although they come from different backgrounds, the two share a passion for oysters and protecting and restoring natural ecosystems.

Oyster and other shellfish were once abundant in the creeks and marshes of Carteret County, but overfishing and environmental changes over the past century have led to a drastic decrease in oyster populations. According to available data from the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries, oyster harvest numbers are only about 15-20% of historic harvest levels recorded in the late 1800s.

Oysters are sensitive to minor changes in the environment, from the salinity of the water to the presence of pollutants, and Mr. Cessna said the already-narrow zones where oysters are able to grow are getting even smaller. That’s a problem because not only are oysters a valuable consumer product, they also help maintain a healthy ecosystem by filtering water – one adult oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water a day.

Dr. Lindquist spent much of his career studying coral reefs, but he turned his attention closer to home in 2009, when he received funding from N.C. Sea Grant to examine the state’s oyster situation. He recruited Mr. Cessna for his wealth of experience in the industry, and together, with the help of graduate students and other researchers, the pair began experimenting with different materials and growing methods.

“That led into multiple projects over four or five years. Part of that was bouncing ideas back and forth, trying to figure out what’s wrong with the oysters, how can we help bring them back, Clammerhead and I,” Dr. Lindquist said. “We came up with an idea for this biodegradable hardscape that could be used to create oyster reefs.”

As Dr. Lindquist and Mr. Cessna worked to develop the new material, they received funding from various sources, including the UNC Small Business and Technology Development Center, NC IDEA and KickStart Venture Services. Their experimentation led them to create a versatile, cement-based substrate they call the “oyster catcher,” which they say has a number of advantages over traditional oyster sills.

Dr. Lindquist and Mr. Cessna claim the oyster catcher substrate is a biodegradable, cost-effective and eco-friendly alternative to traditional oyster growing methods. It produces full-grown oysters in about half the time as other materials and can be used to create living shorelines which establish and restore marsh habitats.

To secure a patent for the new technology, UNC directed Dr. Lindquist and Mr. Cessna to create a company that could lease waters where they could test the material at-scale, and so Sandbar Oyster Co. was born in 2016. Several years into Sandbar’s experiment, the original lease is one of the county’s most productive oyster harvest areas.

Today, Sandbar Oyster Co. operates a number of leases in waterways throughout the region. The original lease is located just west of Beaufort in the Newport River, a quick boat ride away from Gallants Channel. Mr. Cessna and Dr. Lindquist call the 1.3-acre lease “The Lump.”

At The Lump, oysters grow abundantly on the oyster catcher surfaces Mr. Cessna and Dr. Lindquist have set up over the past few years. The substrate can be molded into various shapes and sizes, and Mr. Cessna points out where they have experimented with arranging the shapes into different patterns at The Lump. In one corner of the lease that Mr. Cessna calls “The Garden,” Dr. Lindquist has been experimenting with growing marsh grass among the oyster clusters.

Eventually, the oyster catcher substrate will disintegrate entirely, leaving behind a self-sustaining, productive oyster reef. That process, from seeding to productive oyster habitat, happens relatively quickly, within about 12-15 months. Growing oysters to market size using traditional methods and materials can take up to two years.

Mr. Cessna predicts the current setup on The Lump could produce up to 30-40 million oysters a year.

At an adjacent lease named “The Spa,” Mr. Cessna and Dr. Lindquist recently placed dozens of rows of oyster catchers in the form of discs – they call them “cow patties” – where oyster larvae called spat have just begun to attach. Mr. Cessna guesses once the lease becomes productive, the setup at The Spa could produce an additional 4-5 million oysters a year.

At The Lump, Sandbar grows a varietal of oyster Mr. Cessna named Wild Pony after the horses that freely roam nearby Shackleford Banks.

The company’s flagship product, however, is a green-gill oyster they’ve named the Atlantic Emerald. The Atlantic Emerald is grown in North River, slightly east of Beaufort, where a microscopic organism known as Haslea ostrearia bloom annually and give the oyster its signature green color. As oysters feed in waters teeming with Halsea, the plant’s rich blue pigment stains their gills green.

advertisement

Sandbar Oyster Co. also grows another green-gill oyster varietal in Core Sound known as the American Jade in Core Sound, which Mr. Cessna said is slightly less salty than the Atlantic Emerald.

Until recently, Mr. Cessna said there was not much of a market for green-gill oysters in North America because consumers were turned off by the color. He said green gills have been a delicacy in France for centuries, but they never caught on the U.S. because of misconceptions that they were diseased or rotten.

Mr. Cessna said the truth about green-gill oysters couldn’t be further from the perception, and for decades he tried to convince others to try them. A few years ago, food writer Rowan Jacobsen gave green gills a chance and helped spark interest in the oyster with an article in Tasting Table magazine.

“The response was great,” Mr. Cessna said. “…After that came out, we started getting a few calls and interest started growing.”

Mr. Cessna began bringing Atlantic Emerald samples to various events, and they have been a hit, so far. They still aren’t widely available, but demand for the green-gill oysters has increased exponentially in the past couple of years, and Mr. Cessna expects this will be a banner year for the varietal.

Although Sandbar Oyster Co. is making a name for itself with its premium oyster offerings, Mr. Cessna and Dr. Lindquist consider the habitat restoration and environmental protection side of their business the most important work they do.

“To us, the Atlantic Emerald is a calling card that brings attention to our other stuff, and we consider the substrate manufacturing and the restoration and shoreline protection much more important than having the best oyster out there. We’re lucky to be in both positions,” Mr. Cessna said. “…It’s been a challenge every day and I love that challenge. If we have a good impact on the environment, the economy, social standings, then I can sleep pretty good with that. I feel like I was given a gift that I can use to help others, then I have a responsibility to do that, and I feel like I’m facing it.”

For more about Sandbar Oyster Co., visit sandbaroystercompany.com or email Dr. Lindquist at niels@sandbaroystercompany.com.